How the surrealists used randomness as a catalyst for creative expression

A century ago, the French writer and poet André Breton penned his ‘Manifesto of Surrealism,’ launching an art movement known for creating bizarre hybrids of words and images.

A century ago, French writer and poet André Breton penned his “Manifesto of Surrealism,” which launched an art movement known for creating bizarre hybrids of words and images.

These juxtapositions, often generated through chance, were thought to stimulate the unconscious mind to cultivate new insights.

Man Ray’s puzzling photographs of out-of-focus collages or Salvador Dalí’s jarring paintings of melting clocks and elongated elephants were typical of the form.

As I detail in my book “The Random Factor,” much of life is influenced by randomness – from natural evolution to the selection of friends and spouses. The surrealists, too, made randomness a cornerstone of their artistic practice.

Manifestations of the marvelous

In 1928, the artist Otto Umbehr, known simply as Umbo, snapped a picture from his window that randomly captured the street scene below.

The power of the image – “Mystery of the Street” – comes not from its content but from its orientation. When Umbo developed the photograph, he decided to invert it. The result is an ordinary image of people but with their elongated shadows taking on a startling life of their own.

As contemporary photographer Sandrine Hermand-Grisel writes, “The surrealists question the documentary value of photography. They perceive its capacity to capture the manifestations of the marvelous that can happen at random.”

Surrealist painter Max Ernst often employed the technique of “decalcomania,” which involved applying a layer of paint to a surface, such as glass, and then transferring the wet paint directly onto the canvas. Some of the paint would stick – some of it wouldn’t. No matter: Ernst would build off the random patterns and textures to create the painting.

Out of many, one

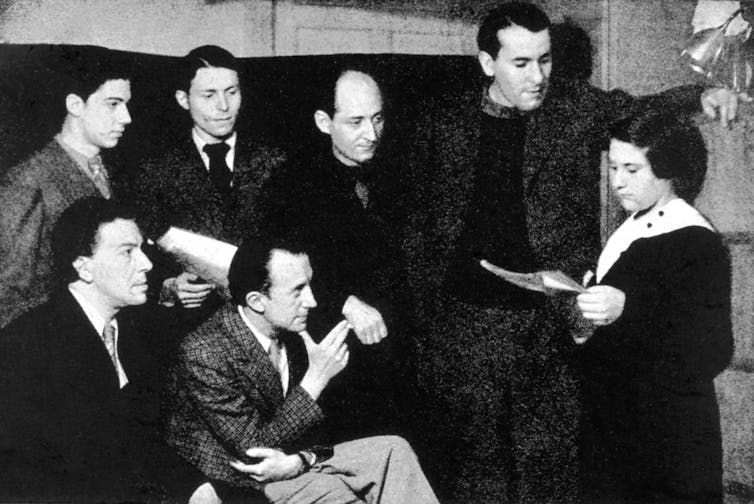

Another surrealist practice involving randomness came to be known as the “exquisite corpse.”

The earliest version of the collaborative exercise involved gathering a small group of friends and dividing a sentence into various parts of speech, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs and so on. Each part of the sentence would be assigned to one person. The first person would write down a word for their part of the sentence, fold the paper over and hand it to the next person. The second person would then select their word, not knowing what the first person had written down, and pass the developing sentence onto the next person.

In this way, the sentence would be written as it traveled around the room without anyone knowing what the sentence looked like until it was completed and someone unfolded the paper.

The process results in sentences that people wouldn’t concoct on their own. According to legend, the first sentence constructed by André Breton and his fellow surrealists read, “The exquisite corpse shall drink the new wine.”

Random by design

The principle of the exquisite corpse has been applied to other creative ventures.

The Blackwing 602, manufactured by the Eberhard Faber Pencil Company, is one of the most iconic pencils of the 20th century. Pitched with the tagline “Half the Pressure, Twice the Speed,” it became known for the quality of its graphite and its unique, rectangular eraser.

The Blackwing was a favorite of many writers and artists, including John Steinbeck, Leonard Bernstein and animator Chuck Jones of “Looney Tunes” fame. But Eberhard discontinued the Blackwing pencil in the 1990s.

Fast-forward to 2010. The California Cedar Products Company reintroduced the Blackwing 602. In March 2018, the company designed a limited edition Blackwing pencil to commemorate the surrealists by using the exercise of the exquisite corpse to fashion a new pencil.

They divided the parts of the pencil into five sections: graphite, barrel, imprint, ferule and eraser. The first person of the design team selected the graphite. The second person, who was unaware of the first person’s choice, designed the barrel, and so on.

The result was a stunning pencil – one of my favorites – that would have never existed were it not for a willingness to surrender to randomization.

The pencil has a rose-colored barrel with teal imprint, a silver ferule, a blue eraser and extra-firm graphite. The company dubbed it the Blackwing Volume 54 in honor of 54 Rue du Chateau in Paris, the address for the house where that very first exquisite corpse exercise took place.

A leap of faith

Musicians, filmmakers and graphic designers also incorporate randomness into their work. The composer John Cage often used randomness and chance in his compositions. In one piece, a pianist sits silently for 4 minutes and 33 seconds, compelling the audience to experience the random coughs and rustling in the room.

In his “Imaginary Landscape” series, random elements produced by electricity are part of the performance; for instance, during one performance, Cage placed 12 radios on the stage, each tuned to a different station, and played them simultaneously. In describing this process, Cage wrote, “Chance, to be precise, is a leap, provides a leap out of reach of one’s own grasp of oneself.”

As museums around the world celebrate the centennial of the birth of surrealism, it’s important to recognize that embracing randomness allowed these artists to think outside the box. The use of chance as a tool of creativity continues to this day, providing a helping – and surprising – hand, taking artist and audience to places heretofore unknown.

Mark Robert Rank does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Read These Next

ChatGPT and the movie ‘Her’ are just the latest example of the ‘sci-fi feedback loop’

Science fiction and technological innovation feed off each other in an ongoing back-and-forth that can…

5 ways anti-diversity laws affect LGBTQ+ people and research in higher ed

Laws that scrap diversity, equity and inclusion programs on campus are likely to result in less support…

For many Olympic medalists, silver stings more than bronze

Researchers used AI to analyze photos of Olympic medalists and found that bronze medalists appeared…