Will the GOP let Congress send money to states and cities reeling from the pandemic? 4 essential rea

The pandemic isn't just a health disaster. It's a disaster for cities and states, where the money to run government that normally comes in every year has evaporated. Congress may or may not help.

As Congress wrangles over a new coronavirus relief bill, it’s not only unemployed Americans who are facing financial disaster in the absence of new federal aid.

States and cities are, too.

Since early April, The Conversation has featured a series of stories on the devastating economic consequences of the coronavirus on the places where Americans live and work. Tax revenues – which pay for a lot of local government services – have plummeted, health-related costs have soared and both have led to government spending cuts that one state, New York, said had “no precedent in modern times.”

Democrats in Congress want to send $1 trillion to help out states and cities in their version of the relief bill. The GOP’s bill has, so far, no money for states and cities, though reportedly its position has moderated recently. Here are four stories that walk you through the problems faced by governments across the country.

1. Who wants to be a governor?

Ray Scheppach teaches public policy at the University of Virginia. But for almost three decades, he ran the National Governors Association. He gets how states run and what they need.

“‘Governors Have the Best Political Jobs in America’ is the name of one of my lectures in a leadership course I occasionally teach at the University of Virginia,” he writes. Governors have broad appointment powers, they have substantial say over state budgets and they have the line-item veto, which allows them to strike individual items out of their legislature’s budget. What’s not to like?

But now, writes Scheppach, he might call that lecture “Governor, why did you want that job anyway?”

The magnitude of the fiscal crisis for states was just beginning to emerge when Scheppach wrote his story in early April. His predictions were dire – and prescient: Rainy day funds would quickly evaporate; sales, personal and corporate income tax revenues would dive; Medicaid spending would explode, all leading to budget cuts, tax hikes and the desperate need for federal assistance.

2. The state pension problem wasn’t bad enough already?

In late April, a handful of GOP senators wrote to the president to say they didn’t want the federal government to give additional aid to states hard-hit by COVID-19.

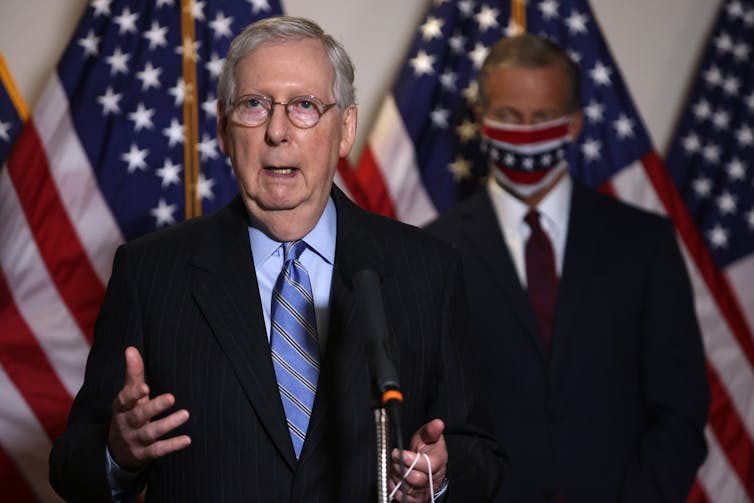

“We believe additional money sent to the states … will be used to bail out unfunded pensions, reward decades of state mismanagement, and incentivize states to become more reliant on federal taxpayers,” they wrote. GOP Senate leader Mitch McConnell endorsed this view.

It was one of the very few public discussions of an enormous and complex problem facing many states before the pandemic descended.

In his second story about the coronavirus’s economic effects on states, Scheppach describes how COVID-19 could turn the state pension problem into a crisis. To do that, he takes on the tough job of explaining just what that pension problem is.

“The problem – and it’s a big one – is that many of the public employee pension plans run by states don’t have enough money in them to make upcoming pension payments to retired state workers,” Scheppach writes.

If you’ve been waiting for a reader-friendly guide to a subject that includes phrases like “unfunded actuarial accrued liability,” Scheppach’s your guy. He skips over accountants’ terms and lays out the bottom line: “In 2017, total pension liabilities for all states was US$4.1 trillion and assets were $2.9 trillion.”

COVID-19 will make those numbers much worse.

With governments obligated to pay pension costs, states will have to shift their spending “away from schools and all the public services that state residents expect their tax dollars to pay for,” Sheppach writes.

3. The cuts are coming … and coming

State budgets usually run from July 1 to June 30. So American University public administration and policy scholar Carla Flink waited until early July to send us her story on how states were handling the financial crisis so she could see what those budgets looked like.

In a word: ugly.

Flink found that state and local governments need to cut spending as much as 15% or 20%, and possibly raise taxes, to make up for the hundreds of billions of dollars lost over the next two to three years because of the pandemic.

“Those cuts have already included reducing the number of state and local jobs – from firefighters to garbage collectors to librarians – and slashing spending for education, social services and roads and bridges,” she writes.

4. Coming to a city near you

“U.S. cities are fast running out of cash,” write Mark Davidson at Clark University and Kevin Ward at the University of Manchester.

The two geographers study city budgeting, and they write that the pandemic will reduce local government revenues by an estimated US$11.6 billion in 2020 and declines will continue into 2021. That means bankruptcy for cities in the poorest shape, Davidson and Ward warn – and big cuts even for those who don’t go down that road.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

“The pandemic has hit budgets so hard that even cities in relatively good financial health – including those with rainy day funds to help them through an emergency – will face significant changes to staffing and services,” they say.

City spending – on everything from salaries to pensions, road repairs, borrowing, park maintenance, policing and libraries – will have to be cut.

“Everyone involved faces great uncertainty,” write the scholars, in a summary that could just as easily apply to anxious state government officials across the country – as well as the residents of their states, who will bear the consequences of the pandemic’s financial devastation for years to come.

Read These Next

Will the lights go out on Cuba’s communist leaders? With fewer options to prop up economy, their fut

Blackouts on the Caribbean island are shining a light on a crumbling economy that the nation’s communist…

Kristallnacht’s legacy still haunts Hamburg − even as the city rebuilds a former synagogue burned in

Questions about how to represent German Jews, past and present, have complicated plans to rebuild the…

Only 5.3% of welders in the US are women. After years as a writing professor, I became one − here’s

Being a woman in a welding and fabrication shop means finding workarounds for getting tasks done.